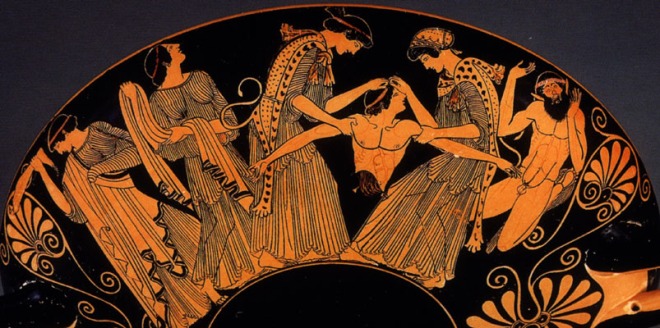

Aristophanes. Lysistrata. 411 BCE. Ancient Greek antiwar comedy of the sexes.

Aristophanes. Lysistrata. 411 BCE. Ancient Greek antiwar comedy of the sexes.

I took 75 minutes to devour this deliriously ribald comedy of the sexes from the classical era’s finest comic playwright, ranking higher even than Petronius and Juvenal. This play features an Athenian heroine called Lysistrata, who persuades girls and matrons all over Greece to halt the sanguine Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens by refusing to sleep with their husbands until the latter negotiate a peace treaty. These unorthodox antiwar activists occupy the Acropolis and taunt and allure the men until, frantic with lust, the men give in and make peace. Afterward . . . well, everyone just gets “so happy together,” as The Turtles would sing.

Lysistrata is a fantastical farce that Aristophanes makes wildly convincing. The wordplay and situational comedy (men walk around trying to hide their huge erections under their cloaks) are sure to evoke gut-wrenching guffaws of mirth and astonishment. But the antiwar message is dead serious; readings of the play proliferated when the USA invaded Iraq in 2003.

Now, ribaldry may be an art form degenerated from the sublime climaxes of Greek Victorianism (Aeschylus) and modernism (Euripides), but it is precisely because of its postmodern sensibility—its iconoclasm, playfulness, feminism, and mockery of male sexuality—that Lysistrata is the funniest, most uninhibited play I have ever read. Never mind the Sixties—it was Aristophanes who first called upon humanity to “make love, not war”!